The profession is taking steps to improve racial inclusion and equal opportunities

The Black Lives Matters movement was one of the few things that managed to divert attention away from Covid-19 this summer. It made us all examine our values and with Black History Month just over, it seems a good time to look at ethnic diversity in the legal profession in Scotland.

The 2018, Law Society of Scotland’s Profile of the Profession shows that its members are predominately “white – Scottish”. Only 3 per cent of the 2,700 respondents described their ethnic group as other than “white”.

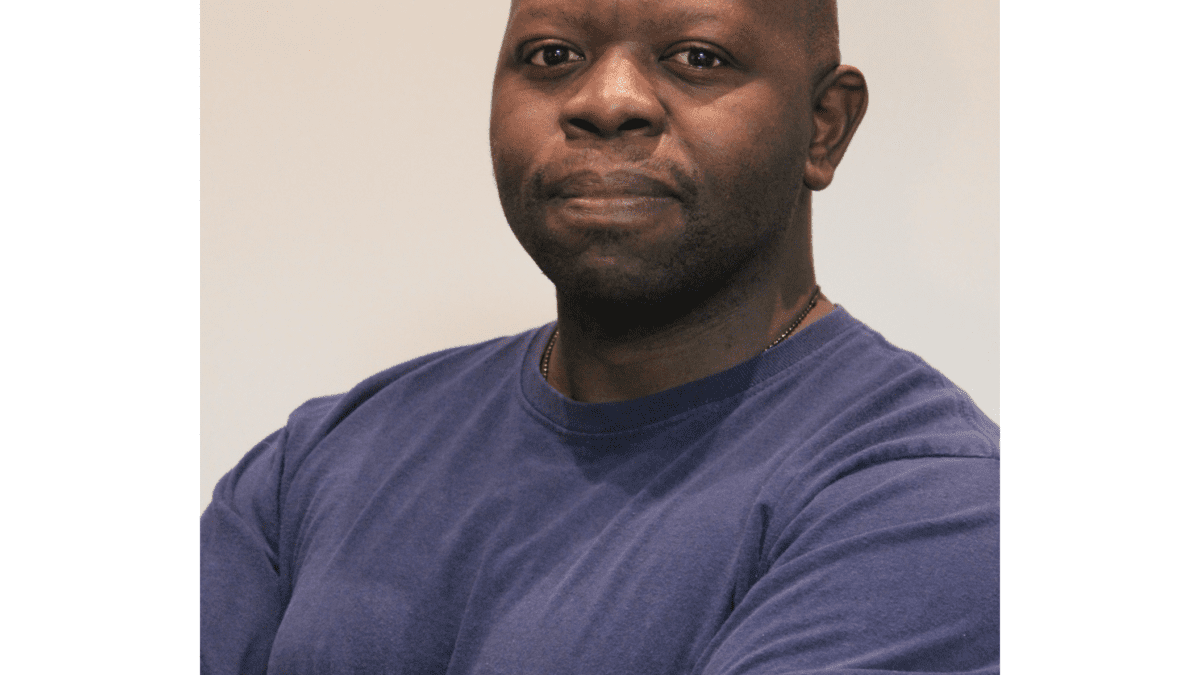

This does not surprise Tatora Mukushi, a dual-qualified human rights solicitor currently leading Shelter Scotland’s Migrant Destitution Project.

When he moved to Scotland in 2014 he realised that he was a “remarkable rarity”. As far as he knows, he is one of only four black lawyers in the Central Belt.

In his professional life the colour of his skin has rarely been something Mukushi thinks about, but Black Lives Matters and the death of George Floyd this summer has changed things.

“People are asking professionally, and personally, for advice and insight which has meant I’ve been thinking about my role. Maybe I need to say something, maybe I should know more. It makes me more aware of it than a year ago.

“In the past, other people’s interest in it was incidental. I might have to spell my name and they become curious about that.”

But in terms of his career, Mukushi says: “My skin colour has been neither a bonus nor a hindrance to my professional progression in Scotland.”

Although the ethnic make-up of the profession broadly reflects Scotland’s wider population, the issue of increasing diversity has been moving up the agenda over the years.

“We have a statutory objective to promote equal opportunities in the profession across all the protected characteristics. However, our interest in equality, diversity and social mobility issues predates the formal objective, and we have consistently considered this work to be the ‘right thing to do’,” explains Elaine Macglone, the society’s equality and diversity manager.

“We’ve been trying to improve racial inclusion in the profession in a number of ways. This year, we are collecting data on ethnicity, religion, disability, social background and sexual orientation at Practising Certificate (PC) renewal for the first time. We’ll also be launching a new group to consider how we better improve racial inclusion imminently.”

Susan Murray, convener of the society’s equality and diversity committee, said: “By including diversity data in the annual PC renewal, we will ensure a regular, reliable evidence base that helps us to set policy, trace trends and measure our progress towards a more inclusive profession that reflects the society it serves.”

In 2017, the Scottish Ethnic Minorities Lawyers Association was formed with the support of the Law Society of Scotland and the Faculty of Advocates. It focuses on the mentoring, networking and support of ethnic minority lawyers to encourage better and more diverse representation in all branches of the legal profession.

Another initiative is a contextualised recruitment tool. The Law Society of Scotland has partnered with diversity recruitment specialist Rare to give member firms access to it.

“The software identifies people that wouldn’t necessarily come over as exceptional in a regular application form but actually they have shown exceptional resilience or determination to get where they are,” says Heather McKendrick, the society’s head of careers and outreach.

It helps firms uncover any external factors that may have contributed to a candidate’s grades and experience. And Rare has recently set up a race fairness commitment which aims to give everyone from all backgrounds an equal chance to succeed.

“It mirrors universities’ contextualised admissions so that when graduates are applying for their first professional roles, it continues the good work. I do think contextualised recruitment is a really pragmatic way to make a big difference,” adds McKendrick.

Morton Fraser, one of the firms which took part in the pilot last year alongside Dickson Minto, has already found it helped select candidates it would not normally have identified.

Martin Glover, the firm’s director of HR, said: “Where we previously might have only focused on grades and relevant work experience, we are now able to see that someone might have great potential, but due to their circumstances were unable to take an unpaid internship or relevant work experience because they needed to earn money to support their family or pay their rent.

“This type of recruitment is a massive leap forward in promoting social mobility and ensuring that we recruit on a level playing field.”